Baking is a complex interplay of science (ingredients) and time (method). For a successful commercial bakery, the operational choice of when to ferment the dough dictates everything: the final product’s quality, labor scheduling, required equipment, and ultimately, the business’s profitability.

This article dissects the core baking methods—Direct Baking and Delayed Baking (Retardation)—examining their operational impacts and the foundational role of fermentation agents like yeast and sourdough.

I. Core Fermentation Agents: Yeast vs. Sourdough

The first decision a baker makes is the source of the rise. This choice fundamentally dictates the necessary time and complexity of the workflow.

| Agent | Characteristics | Advantages | Drawbacks |

| Commercial Yeast | Fast-acting, reliable, single-strain consistency. | Speed: Quickest turnaround time, high predictability. Consistency: Reliable results for standardized products. | Flavor: Less complex, often one-dimensional. Shelf Life: Tends to stale faster than sourdough products. |

| Sourdough Starter (Wild Yeast/Bacteria) | Slow-acting, produces lactic and acetic acids for flavor. | Flavor: Deep, complex, tangy profile. Digestibility: Enhanced nutrient breakdown (due to long fermentation). Shelf Life: Superior keeping qualities due to acidity. | Time: Requires significant time for proofing (often 12+ hours). Maintenance: Starter requires daily care and feeding. Consistency: Highly sensitive to temperature and environment. |

Impact on Planning: Sourdough necessitates long-term planning and scheduling, often making it incompatible with fast, direct methods, while commercial yeast allows for flexibility and rapid reaction to sudden demand.

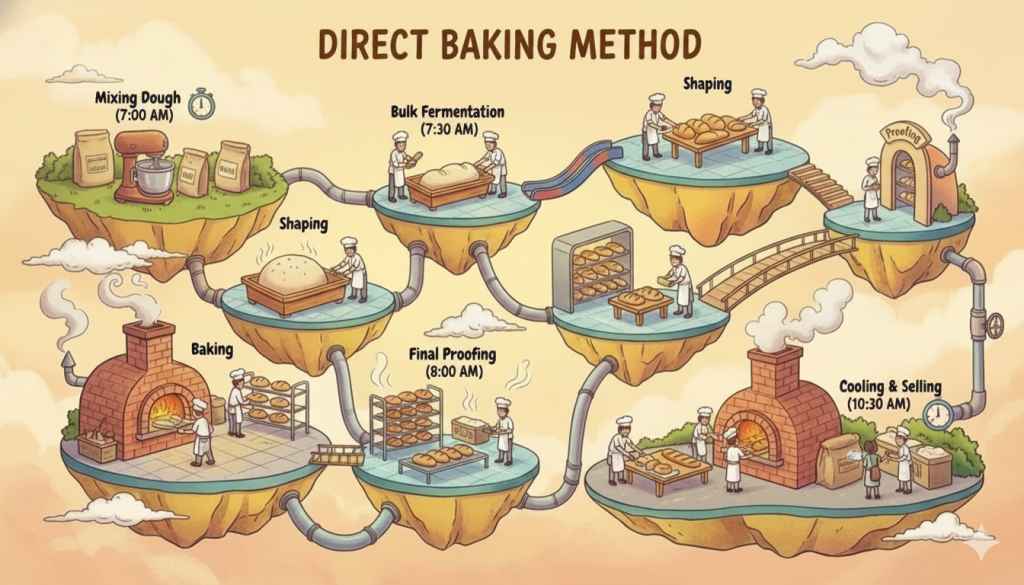

II. Baking Method 1: Direct Baking

The direct method completes all dough processes—mixing, proofing, shaping, and baking—within a single, concentrated workday, typically 4–8 hours.

Operational Workflow

| Step | Day & Time | Activity |

| Day 1 | 1:00 AM – 4:00 AM | Mixing, Bulk Fermentation, Shaping (fast-paced) |

| Day 1 | 4:00 AM – 6:00 AM | Final Proofing |

| Day 1 | 6:00 AM Onward | Baking, Cooling & Selling |

Advantages & Drawbacks

| 👍 Advantages | 👎 Drawbacks |

| Simplicity and linear workflow. | Blander Flavor due to shorter fermentation time. |

| Responsiveness to same-day demand fluctuations. | Intense Labor Shift concentrated into very early, premium-wage hours. |

| Minimal need for specialized refrigeration equipment. | Less developed crust and crumb structure. |

III. Baking Method 2: Delayed Baking (Retarded Fermentation)

This method intentionally slows the fermentation process by placing the dough in a cold environment (e.g., 4-10°C / 39-50°F) for 12–72 hours. This retardation dramatically improves flavor, crust, and crumb structure while fundamentally altering the bakery’s labor schedule.

A. Delayed Bulk Rest (Cold Bulk Fermentation)

In this approach, the entire mass of dough is retarded before shaping.

| Operational Step | Day 1 (Prep Shift) | Day 2 (Bake Shift) |

| Mixing | Completed. Dough goes immediately into the retarder. | N/A |

| Retardation | Bulk rest for 12-18 hours. | N/A |

| Shaping | N/A | Shaping is completed early on Day 2, using the cold, stiff dough. |

| Final Proof | N/A | Requires a longer final proof (warm-up) before baking. |

| Goal | Prioritizes maximum flavor and consistency of cold-shaped products. |

B. Delayed Preshaped Rest (Cold Final Proof)

In this approach, the dough is divided and shaped on Day 1, and the final shaped loaves are retarded.

| Operational Step | Day 1 (Prep Shift) | Day 2 (Bake Shift) |

| Mixing & Shaping | Completed. Shaping occurs during a more standard afternoon shift. | N/A |

| Retardation | Final proof (as individual loaves) for 12-18 hours. | N/A |

| Shaping | N/A | N/A |

| Final Proof | N/A | Loaves go directly from the retarder into the oven (or after a very short warm-up). |

| Goal | Prioritizes labor efficiency and a rapid start to the Day 2 bake shift. |

Advantages & Drawbacks of Delayed Baking (Overall)

| 👍 Advantages | 👎 Drawbacks |

| Superior Flavor and keeping quality. | High Capital Cost for large-capacity industrial retarders. |

| Flexible Labor: Spreads labor over two shifts (afternoon prep, morning bake). | High Energy Consumption for prolonged refrigeration. |

| Allows fresh, hot bread to be offered throughout the day. | Requires accurate long-term demand forecasting (days in advance). |

IV. Impact on Bakery Shop Planning

The choice of baking method fundamentally defines the bakery’s operational blueprint:

- Labor Scheduling: The delayed method is key to attracting and retaining skilled bakers, as it shifts the most intense labor (shaping/baking) to later, more humane morning hours (e.g., 4 AM vs. 1 AM).

- Space & Equipment: Direct baking focuses on oven and proofer space. Delayed baking mandates significant investment in and space allocation for industrial retarders. The size of the retarder often becomes the limiting factor for production capacity.

- Product & Pricing: Sourdough and retarded methods allow for a premium price point due to demonstrably superior quality. Direct methods are better suited for cost-sensitive, high-volume items that rely on turnover.

- Forecasting: Delayed methods, particularly Preshaped Rest, require excellent demand forecasting, as an entire day’s inventory must be committed and prepared 12–18 hours in advance.

V. Conclusion: The Hybrid Approach

Few successful modern bakeries rely solely on a single method. The most profitable model often uses a hybrid approach:

- Delayed/Sourdough Methods: Reserved for signature, high-quality loaves (e.g., boules, specialty sourdoughs) that command a premium price and form the backbone of the bakery’s reputation.

- Direct Methods (with Yeast): Utilized for high-volume, quick sellers (e.g., dinner rolls, simple sandwich bread) to meet immediate demand and optimize daily volume.

Ultimately, the best baking method is the one that transforms the baker’s scientific skill into a sustainable, finely-tuned production facility where time, not just flour, is the most valuable ingredient.